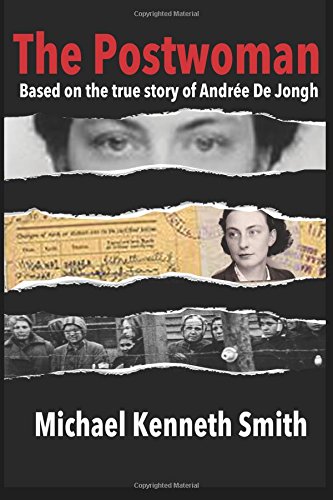

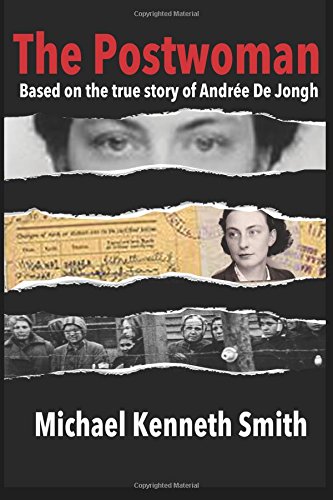

The following is excerpted from The Postwoman—based on the true story of French Resistance fighter, Andrée De Jongh. Available on amazon.com in paperback and as an ebook.

The following is excerpted from The Postwoman—based on the true story of French Resistance fighter, Andrée De Jongh. Available on amazon.com in paperback and as an ebook.

June 1940

The young English soldier’s face lit up when Dedee approached his bed. His shrapnel-lacerated arm had mostly healed, and he was due to be released soon. She frowned, and put her finger to her pursed lips. The door to the fifty-bed ward burst open and two German SS officers entered. Dedee quickly dabbed a yellowish red fluid on the Englishman’s bandages. The smell was disgusting.

The two Germans were doing their weekly inspection of the soldiers, most of whom had been injured in the recent fighting near Dunkirk. When released from the hospital, the English soldiers would be shipped to workcamps in Germany. The SS officers stopped at each bed and asked to see the patient’s wounds. If they thought the wounds were healed, they marked their chart, and the patient would be shipped out the next day. When the SS officers approached the bed by which Dedee stood, they didn’t even ask to see the wound. Wrinkling their noses at the smell, they quickly moved on.

Dedee winked at the Englishman and left the ward. She thought back to when she was a little girl and a neighbor boy would always take her bicycle without her permission. She’d smeared Limburger cheese on the handlebars, and it never happened again. Rumors were the workcamps were more like death camps. The Germans were using the labor of English soldiers to bolster the Weimar’s war effort. Dedee found that idea abhorrent.

Later, on the way home to her flat, she passed the home of one of the attending Belgian doctors, a longtime friend of her father’s. She knew him to be an excellent doctor, but also a passionate patriot who despised the Germans almost as much as she did. She knocked on his door. She was thinking there had to be a way to help the British soldiers, or at least keep them from being sent to labor camps. The doctor answered and immediately let her in.

“Quite a stunt you pulled today,” he said with a smile. “We still haven’t got that smell out of the ward. I can still smell it on my clothing.” He offered tea, which she accepted. They sat in his kitchen in awkward silence.

The doctor knew Dedee well enough to know her visit was not a social call. “I think that poor soldier would’ve been shipped out tomorrow if you hadn’t saved the day,” he said, trying to get a conversation started.

“Do the other doctors feel the way you do, Doctor?” She asked.

“Almost all. But we can’t keep the patients in the hospital forever,” he said. “Maybe we could hide them somewhere.”

“Yes, but where?” she asked. “There would be hundreds. Maybe thousands.”

“Anyplace big enough for that would be discovered,” he said.

“We have an extra bedroom at my parent’s place. We could handle one or two,” she said.

“My wife and I do, also—but the risk is huge. The consequence of getting caught would be prison…or worse.”

Dedee hardly noticed the rain as she walked back to her father’s apartment in the Schaerbeek District. She traveled this route twice a day, and despite the discomfort caused by her wet clothing, her mind reeled. A trained commercial artist, Andrée’ (Dedee) de Jongh was a petite young woman, standing five feet two inches tall. She was svelte, and attractive. Her short brown hair was naturally curly, and her blue eyes flared with intensity, intelligence, and determination. When the Belgian hospitals had started filling up with British wounded during the Dunkirk debacle, she’d volunteered as a nurse, and was appalled by the huge number of British soldiers who filled their hospitals. Both Dedee and her father were sickened by how quickly their country had succumbed to the German blitz and what many considered a premature Belgian surrender by King Leopold III to Nazi Germany. Dedee frequently wrote letters to the parents or families of her patients, notifying them that their son or husband was alive. She hated the Germans, and it was that hatred that would keep her focused through the troubling times ahead.

As she turned a corner and started the slow uphill grade to her house, she noticed a Kübelwagen parked on the opposite side of the street. The engine was running and both windshield wipers were on high and out of sync. Blue smoke came out of the exhaust, and rain drops spat and steamed when they hit the hot pipe. Both doors were open, and Dedee could see no one in the vehicle, but she heard voices. Then she heard a man screaming.

As she crossed the street for a better view, Dedee saw two German soldiers beating an older man. One was hitting the man with a schlagstock and the other was kicking him with his boot. The man, who was trying to protect himself with his hands and arms, had a star sewn onto his jacket.

One of the Germans kept yelling, “Verdammter Jude!” Damn Jew! over and over.

Dedee approached the Kübelwagen from the opposite side and reached in through the open door and released the center-mounted parking brake. The vehicle started to coast backwards, gradually picking up speed.

When Dedee screamed, the two soldiers looked up and immediately bolted after their truck, leaving the poor man alone, struggling to stand.

When she approached the man, he stood unsteadily.

With her arm around him in support she whispered, “Is your home nearby?”

When he said it was just around the corner, she helped him to his door and wished him good luck.

He unlocked the door, and taking both her hands in his, said, “Toda raba,” Thank you very much.

Only after she arrived at her father’s house did Dedee realize she was soaking wet.

The gentle rain that had been falling when she started had turned into a downpour, and she had hardly noticed.She changed out of her wet clothes and put on her robe, wrapped her hair in a towel, and began fixing dinner for the herself and her father.

She was comfortable in the kitchen. Moving efficiently, she prepared a fish stew that her mother often served when it was cold and rainy. Food supplies had already become scarce as German officials confiscated much of what was available, to be shipped back to Germany. Dedee was thankful that her mother had wisely stocked up on canned goods, anticipating shortages.

Her mother was attending her sick sister in Ghent, about fifty miles north, and they did not know how soon she could return.

Her father, Paul, arrived through the back door and called a greeting. She could hear him removing his rain slicker and hanging his umbrella to dry.

Dedee smiled, thinking her father at least had enough sense to stay dry in the rain. He was fifty-eight years old, wore thick spectacles, and his gray hair was combed back, creating a scholarly look worthy of his teaching profession. In addition to being an administrator at a boys school, he taught physics to the seniors, and when Dedee was younger, they spent hours talking about how and why mechanical things worked the way they did. The two of them also agreed on almost all things political: a strong government, good education, social programs for the poor and underprivileged, and most of all, women’s rights.

Paul could see that Dedee was excited about something. He asked, “How was your day?”

She told him about the run-in with the two German soldiers at the hospital and laughed when she described the way they had hastily left when they smelled the pongy fluid taken from a man who had drowned.

Then she related the incident with the drunks in the Kübelwagen. Paul said he had heard of several other such incidences. He related how the Germans occupied Belgium in The Big War, friendly at first, then increasingly aggressive, especially with women. They both knew their behavior would only get worse…A lot worse.

“Paul, I stopped by the flat of one of our staff doctors today on the way home,” Dedee said. Since early childhood, Dedee had called her father by his first name. Paul had insisted on it. It was a tradition in his family, and Paul thought it brought everyone to the same level, for easier conversation. She called him ‘father’ only when she wanted to express her love for him.

Paul knew Dedee was finally getting to what she really wanted to say, and what she was so excited about. “And?” he asked.

She smiled. “We can’t let these wounded British soldiers go to German workcamps,” she said. “All that accomplishes is the Germans get stronger and we get weaker. We not only have soldiers wounded from Dunkirk, but we also have RAF fliers who have been shot down.”

“This is true, but what do we do? Hide them?”

Dedee was silent. Then she said, “We could ship them back to England…?” It was almost like a question.

“How? Surely the channel is well patrolled,” Paul said.

“Maybe we escort them into Spain.”

“Franco wouldn’t like that,” Paul said, “but their chances would be better in Spain than in Belgium…or France.”

Dedee served dinner, and the two of them continued their discussion for several hours.

Long before dawn, the smell of fresh coffee woke Paul and he walked into the kitchen to see Dedee sitting at the table writing on a tablet. She had a pile of notes stacked up in front of her.

“You been here all night?” he asked.

“Paul, I’ve got it. I think we can do it,” she said.

He poured himself a cup of coffee and sat next to his daughter. He always knew when she was excited because the veins on each side of her forehead stood out.

She started to read her notes. “We’re going to escort them over the Pyrenees. We’ll need safe houses. Lots of them. All along the way. Then we need guides to take them from one safe house to another. We need travel documents. Good ones. We will need coordinators to handle small details. Mountain guides. Most of all, we’ll need money for food, train tickets, and the forgeries.”

Paul frowned. “A bullet through the head if you’re caught. Or even worse, torture.”

She pretended she didn’t hear him. “A friend of mine has a close and willing friend in Anglet, near the Spanish border and…”

“You mean to cross the Pyrenees? What then?” Paul asked.

“San Sebastián, Bilbao, then Gibraltar. The flyers can just get in another airplane and continue to fight,” she said flatly.

Paul thought a moment, then smiled. “Still in love with anybody who flies an airplane, aren’t you?”

Dedee blushed. “Not true. I’d kill a Luftwaffe pilot without even thinking about it.”

Paul studied his daughter from across the table. She was twenty-four years old, soon to be twenty-five. He thought she had the best traits of her mother—especially her determination. He had hoped she would find a good husband and settle down to raise a family, but when the Germans outsmarted the English again at Dunkirk, using the same trick they had pulled in the Big War, she had immediately volunteered as a nurse’s aide, to care for the wounded.

Paul remembered how, at the age of five, Dedee would sit on his lap and beg for him to tell her stories about Jean Mermoz, the famous French fighter pilot who had made himself a hero in Syria when France and Belgium sorely needed heroes after the Great War. She never tired of it. She learned to recognize the various patches on soldiers’ uniforms that signified they were part of an aviation crew, and whenever she saw one, she would try to shake the soldier’s hand.

“Seems like money may be the biggest obstacle,” Paul said, taking Dedee’s plan seriously.

“I’ve got that figured too, Paul,” she said.

“I think I’m afraid to ask,” he said.

She waited to let the drama build. “The British will pay,” she announced.

“The British?”

“Of course. Think of it. Who will benefit by the return of their fliers? They must spend thousands on training, and for each one we return, they will save thousands.”

Paul poured another cup of coffee and sat down again. “You just might be right,” he said. “But, if they finance the operation, they’re going to want to control it. If they control it, we might have difficulty keeping everything secret.”

”I was thinking about that also. I think they will want their fliers back a lot more than they will want control. Especially if we insist that we remain autonomous.”

Over the next several weeks, they made lists of friends and acquaintances who might be willing to help. In addition, and equally important, they made another coded list of friends who might be willing to contribute money. Paul had some meager savings, and they agreed much, much more was required. But even if all their friends were extremely generous, the funds would not be nearly enough. As each day passed, their enthusiasm and commitment increased.

Click to keep reading . . . .

The following is excerpted from

The following is excerpted from  As a junior in high school, without realizing it, my hormones were asserting themselves…peach fuzz on my chin and red blotches all over my fifteen year old face. I liked girls. I liked the way they looked, moved, talked, smelled…everything. I spent a lot of time just thinking about them.

As a junior in high school, without realizing it, my hormones were asserting themselves…peach fuzz on my chin and red blotches all over my fifteen year old face. I liked girls. I liked the way they looked, moved, talked, smelled…everything. I spent a lot of time just thinking about them.

This week’s #SaturdayScene features Caitlin Hamilton Summie’s

This week’s #SaturdayScene features Caitlin Hamilton Summie’s  This week’s #SaturdayScene features

This week’s #SaturdayScene features  This week’s #SaturdayScene is a continuation of last week’s excerpt from Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Eric Foner’s

This week’s #SaturdayScene is a continuation of last week’s excerpt from Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Eric Foner’s