Chapter 1

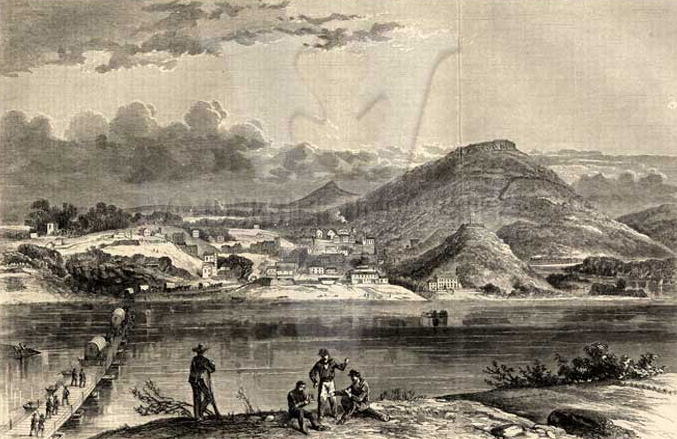

Eastern Tennessee, September 1859

A large sycamore tree projected out of a riverbank ten feet above the water’s edge. Zach and his father were perched on the outcropping, Zach fishing downstream and his dad fishing upstream. Between them, leaning against the tree, was a loaded Enfield musket and a can of worms.

Zach’s father glanced back up the bank behind them. “Son, we have a big copperhead crawling down over the top of the bank right toward us. Do you want him?”

Zach looked back quickly, picked up the gun, cocked the hammer, turned, instinctively aimed the rifle and fired before the stock reached his shoulder. The sound reverberated down the river valley and the headless snake fell down the bank and hit Zach’s father in the back, writhing violently. In his death throes, the large snake wrapped his body around Zach’s father’s waist, tightening its grip. The snake was trying to bite him reflexively, even though he had no means of doing so.

“Don’t know why he’s so mad at you,” Zach said. “You didn’t do anything to him.”

“You are faster with that rifle than most are with a pistol,” his father said laughing.

“Just doing what you taught me, Dad,” Zach said as he pitched the snake into the water.

“ Say, we’re about out of worms, so I’ll walk over to that barnyard we passed a while ago and look for some more. You stay here and fish. We need a few more to have a nice mess to eat tonight.”

Zach was fourteen years old. Every September, he and his father took a week to float a river in eastern Tennessee to fish, hunt a little and live off the land. It always marked the end of the summer and it was the highlight. When Zach was two, his father and mother moved from England to Manchester, Vermont, where his father set up a small gun shop. However, the community turned out to be too small to support the business, so they moved to Knoxville, Tennessee, where the business thrived. This year, they had decided to go down the Obed River, which was a little west of Knoxville, near the small town of Crossville.

Zach was adding a nice bullhead to the stringer of fish when he heard the hoot of an owl. Then he heard the neigh of a horse and immediately looked up, scanning the woods behind him. He grabbed the musket and went up the bank looking for the horse. He was very comfortable in the woods by himself because most summers he hunted every day. Just as he saw the swish of a sorrel’s tail in front of him, he felt the cold steel of a rifle in the middle of his back.

“You are trespassing on private property,” a boyish voice said. “And you are fishing in my private hole. Who are you?”

Zach was shocked that anybody could sneak up on him like that without a sound. He turned around and saw a thin freckle-faced boy with an old flintlock rifle aimed menacingly at him.

“Zach Harkin. We’re just floating down the river like we do every year at this time. We didn’t know this was your private fishing hole.”

“Who’s ‘we’?” said the boy.

“My father and I. He went looking for more worms just over yonder.”

The boy slowly lowered his rifle. “You fishing with worms?”

“Yes, and we’ve caught quite a few.”

“You mean those little things on that stringer there?”

Zach picked up the mocking tone of the boy’s voice. “You know a better way?”

“Sure do. Grubs.”

“Grubs? Never heard of that. Where do you find them?”

“Keep a whole box of them in the ground just above where you where fishing.” The boy studied Zach’s face for a moment. “Want to try them?”

“Sure. We just need a couple more for tonight’s supper.”

“Looking at the size of those you have caught, you could catch a dozen more and you would still starve to death.” The boy gave out a hoot owl whistle and the sorrel horse neighed and came right over to where they were standing. “Say hello to Bonnie.”

Zach realized he had been outsmarted. When he had heard the first owl call, his attention had been drawn by the neigh of the horse, which allowed the boy to sneak up on him from behind. He was impressed. Together they walked back to the bank just above the sycamore tree. The boy kicked the dirt, exposing a wooden lid to a buried box. He reached in and pulled a handful of grubs. “Here try one of these,” he said. “Hook it from the tail to its head. Then cast the grub down on the riverbank and let the grub bounce into the water.”

Zach crawled down to the tree outcropping and after hooking the grub as the boy asked, flung the bait on the bank and watched it tumble into the water.

“Get ready,” the boy said.

Seconds later the line went taut, the pole dipped down and Zach had to hang on. The line swished through the water as the fish tried to get away. Zach feared the line would break and pulled as hard as he dared until the fish finally came to the surface. The boy scrambled down to the water’s edge and expertly grabbed the large black bass by the gills and hoisted it into the air. It weighed at least six or seven pounds.

“Now you have some real supper,” the boy said.

The bass was bigger than all the rest of the fish put together. The boy proudly stuck out his hand. “I’m Luke Pettigrew,” he said. “That’s the way we do things around here.”

“Well, I’ll be…”

Just then Zach’s father came up and stared at the bass. “Guess we have a lot to learn about fishing in this river.”

Zach jumped in. “Dad, this is Luke. He lives around here. I, er, we caught this thing with a grub.”

“Nice to meet you, Luke.”

“He has a whole box of grubs in this box here,” Zach said.

Zach’s father said, “Its getting late in the day. Care to join us for supper? Our camp is just upstream a little ways. Will your folks mind?”

“Nope. My father lets me go out all the time; he won’t care. Whenever I get home, it’ll be alright with him.”

“Okay, let’s get cracking,” Zach’s father said as he led the way back to the camp.

It was dark by the time Zach dropped the large fillets into the sizzling frying pan. The fish had been cleaned and scaled and Luke had found some wild onions.

“You ever do any coon hunting?” Luke asked Zach.

“Not so much over our way. We pretty much stick to other animals like groundhogs, rabbits and squirrels. Besides, don’t you need dogs for coons?”

“Yes, I got a real nice coon dog named Jeff. We like to start out just after it gets good and dark. We walk through the woods and when ole Jeff picks up a scent, off he goes. Some coon hunters like to wait for their dogs to tree the coon, then they ride their horses over to the tree. Me, I like to run with the dog, stay right with him. More fun that way.”

“Now that does sound like fun. Ever try a groundhog from five hundred yards?” Zach countered. “I like to go out just before it gets light in the morning and wait for ‘em to come out of their dens.”

“Five hundred yards? Wow. You must have a special rifle for that. That musket you have won’t go that far, will it?”

“No, it won’t, but dad’s a gunsmith and he has a couple of rifles that are accurate well beyond five hundred yards.”

“Hmmm. I could sit on my back porch and shoot squirrels without even putting my shoes on.”

The sweet aroma of the fish frying wafted through the campsite as all three dug in. Halfway through the supper, the sound of an approaching horse interrupted their enjoyment. Luke immediately jumped up as if he knew what was happening.

A man on a large chestnut rode right into the camp. “Luke, where in the hell have you been?” the man said, “You know you are expected to be home before milking time. I had to get the cows in myself. You are the most irresponsible boy the world. Get home. Now.”

Luke got up promptly and left without a word. He did a back flip onto his horse and rode away.

“Who in the hell do you think you are?” the man said to Zach and his father. “You are on private property and you better not be here when I get up in the morning.” He kicked his horse and disappeared in the night.

Chapter 2 – Zach

March 1862

The sun had just illuminated the far hillside. The spider lines of Zach’s rifle followed the two young groundhogs as they climbed from the hole of their den to the top of the hill. The sun’s rays had melted most of the snow over the last several days. Lying on the ground, using an old butternut log to steady his rifle, Zach felt the cold dampness of the early spring earth through his long wool underwear. The groundhogs’ fur shimmered. They were both healthy and had eaten plenty of corn in the surrounding fields. The distance was about nine hundred yards, and with a muzzle velocity of twelve hundred feet per second, Zach quickly – intuitively – calculated his bullet would take almost two and one half seconds to reach the target. He knew as soon as the first hog was hit, the second would instantly make for his den. Groundhogs could move at lightning speed. His scope was sighted in at five hundred yards; he needed another two feet of elevation to hit his prey. He felt a slight breeze from the left and he moved the scope’s cobweb spider lines slightly to correct. As the second hog rose to survey the surroundings, Zach tried to control his breathing as he always did on long-distance shots, being careful not to fog the lens of the scope. The smell of the thawing earth rose to his nostrils, mixing with the fumes of the gun oil he had applied the night before. Pressing his cheek to the custom-made walnut gunstock, he felt the silky coolness of the wood. His right hand tightened on the rifle grip. It, too, had been custom-made to fit his hand. The bill of his hunting cap shielded his eyes and helped him focus on the target. He relaxed his arm and shoulders to be able to hold the spider lines without movement. He rubbed his trigger finger on the side of the gunstock to increase sensitivity. Finger on the trigger now, he went through his normal ritual… deep breath in… exhale… half-breath in… hold. Steady now, he squeezed the hair trigger and the modified Spencer sent a 52-caliber bullet on its way to his prey more than half a mile away. Before the bullet arrived, Zach, with practiced lightning speed, ejected the shell and pumped a new one into the chamber. Anticipating the second groundhog would hightail it to its den, he moved the spider lines to the mouth of the den fifteen feet below. Compensating for the wind and elevation and before the second hog appeared in his scope, Zach squeezed the trigger again. The smoke from the two shots slowly drifted off and the pungent odor of the black powder permeated the air. He held the spider lines on that spot while he waited the two and one half seconds for the bullet to travel the half-mile. Sure enough, the second groundhog arrived at the hole the exact same instant the bullet arrived. Both groundhogs lay motionless as the echoes of the two gunshots reverberated down the valley once, and then again. Zach broke into a wide grin.

Sitting behind Zach were his father, Tom Harkin, and Jim Luttrell. Both had arrived with Zach some thirty minutes before. Luttrell was the mayor of Knoxville and reputed to be a fine marksman himself. They had seen the whole event with spyglasses that were twice as powerful as the rifle-mounted Davidson 4X scope Zach had used.

Visibly impressed Luttrell said, “Let me see that gun, son.” He rubbed his hand over the fine finish. “Damn, Tom, you are good.”

“Takes more than just a good rifle to hit a target like that, though, Jim. Zach, go get them; we’ll wait here,” Tom said.

Zach, still smiling, got up. Standing his full six feet, he wiped the dirt off his front and took off his cap. His long dark hair fell down over his brown eyes, and he immediately brushed it back. “I can smell it now…roasted groundhog stuffed with apple, yummmm…I’ll be right back.” He took off to pick up the dead quarry. He would skin the groundhogs, and his mother would roast them as only his mother could do.

Luttrell turned to Tom. “Quite a boy you have there.”

“We are proud of him. Pity any animal he’s hunting; they don’t have a chance.”

“Tom, he’d sure make a good soldier. You going to let him sign up?”

“He sure wants to, but Lizzie and I are dragging our feet.”

“He’d make a great sharpshooter.”

“But how could we manage that?”

“Got an idea, Tom. Let me work on it. Think you could hold Zach off for a couple of weeks?”

Several moments later, Zach returned with the groundhogs. Both were nice and fat, about ten to twelve pounds. He took out his hunting knife and quickly skinned and cleaned the animals. He used a unique style he had developed over the years that kept him from getting his hands dirty. After depositing them in a gunnysack, Zach joined the two men on the walk back, about a mile away.

Tom Harkin, a noted gunsmith from Manchester, England, arrived in Vermont with his wife, Lizzie, and his only son in 1857. He had worked at the Whitworth Rifle Company as a design engineer. He loved to work on guns, always trying to improve them, to make them shoot faster, straighter and farther. An independent and adventurous man, he tired of working for a large company and decided to move to America, where he’d been told he’d find great opportunities. He initially chose Manchester, in Vermont, because he reasoned it must have been settled by people from his own Manchester, and the transition would be easier for Lizzie and Zach.

Tom built a small workshop in the family’s new three-room log home and hung out a shingle. Their house was right next to the Charles Orvis home, and to Orvis’ tackle shop, and Tom thought business would be good next to each other. But the village of Manchester turned out to be too small to sustain enough business, so after working hard for almost a year, the Harkins decided to move to Knoxville, Tennessee. They purchased a small house near the corner of Gay and Union Streets and set out a shingle again. The gunsmith commerce was small but steady, and provided a modest income for the family. The scope mount Tom had devised attracted a fair amount of interest. The original Whitmore design had the scope side-mounted, with the rear portion located near the shooter’s eye. While quite effective, this caused a lot of eye bruising from the recoil of the rifle. Tom’s solution was to mount the scope on top of the rifle and slightly forward, allowing the shooter a clearer field of vision and greatly reducing the recoil effect on the eyes. The disadvantage of the top mount was it rendered the conventional open sights on the barrel useless. The shooter did not have the choice of the open sight or the scope. Only the scope could be used with the top mount. As a result, when the target was identified with the naked eye, the time needed to sight in and fire was longer.

Harkin also modified the way the bullets were fed into the firing chamber. Ideally a Sharps rifle would be better suited for long-range shooting, however, he liked the Spencer’s unique design for more rapid firing. The Sharps was a muzzleloader that required a lengthy procedure to load, limiting the shooter to two to four shots per minute, depending on the shooter’s experience. The Spencer, while much lighter, had a hole in the stock from the shoulder butt plate through to the chamber in which the bullets could be stored and held ready for rapid shooting. It was possible to extract a casing and insert another so fast that an experienced user could fire shots every three seconds or less.

The Spencer rifle Zach used had this top-mounted scope. Tom had also installed a longer barrel and forestock to allow for improved long-range accuracy. Also, the barrel was rifled to spin the bullet faster than either the Sharps or the factory-made Spencer. This design change was tested over and over again and proved to be another measurable improvement. Lastly, he added more black powder to the rimfire cartridges, substantially increasing the penetrating power and range. With the mounted scope, the longer, heavier barrel, and increased cartridge power, the gun was limited to prone- or sitting-position shooting. It was a gun ideally suited for fast, long-range shooting. It was a gun ideally suited for a sharpshooter.

That night, the aroma of roasting groundhog permeated the small house as Lizzie Harkin busied herself preparing dinner for Tom and Zach. She was born Elizabeth Medford in Manchester, England, on this exact date forty years ago. Lizzie and Tom were childhood sweethearts. She lived four houses down the street from the Harkin family home and had been attracted to Tom because of his somewhat shy demeanor and independent streak. Lizzie was diminutive in stature and Tom, being slightly over six feet, proved sometimes opposites do attract. She had mid-length auburn hair, dark blue eyes and a beautiful fair complexion. From a very early age, she knew Tom Harkin was going to be the man of her life, and although the job was not too difficult, she made sure he felt the same way. They were married in October 1844. On July 10th, 1845, their only son, Zachary, was born. Complications during childbirth prevented them from having more children, and Zach became the center of their lives.

“When do we eat?” yelled Zach as he sauntered into the kitchen area. “If I don’t eat soon I’ll shrivel up and die from lack of food.” He grinned and hugged his mother.

“As soon as you wash your hands, set the table and pour some water, we will be ready,” said Lizzie. “And you might want to call your father and have him wash up, also.”

After they were seated around the table, Tom raised his water in a toast and said, “Lizzie, here’s to your next forty years.” Birthdays were not celebrated in the Harkin house, and Lizzie flushed. She was not surprised Tom remembered. He always remembered.

During the meal, the conversation was stilted. The war weighed heavily on their minds, but no one said anything. Finally, Zach managed to say, “Father?” He desperately wanted his parent’s – particularly his father’s – permission to sign up.

Tom took a deep breath. “Son, your mother and I dearly do not want you to go off to this senseless war. We do not believe in this war. If some of the Southern states want to secede from the Union, why should we sacrifice so much to keep them in. Some would say they have a clear right to secede anytime they want to.”

“I could forbid you to go,” Tom continued. “However, you just might run out there and sign up anyway. You would end up serving under some city-bred officer who wouldn’t know beans about war and tactics. Jim has a couple ideas and promised to get back in a couple weeks. Then you can decide.”

On a rainy afternoon a several weeks later, Jim Luttrell strode into Tom’s little shop.

“Hello, Tom. Have any hot coffee? I’m soaked.”

Lizzie always kept a pot of coffee on the stove so customers could sit and relax while they talked about guns. Everybody loved to talk guns, and everybody wanted to talk to Tom about guns because he was the recognized resident expert.

Tom poured a mug for Jim and another for himself.

Jim started. “Tom, as our mayor, I have become a friend of John Sherman, who was a U.S. congressman and now has been elected to the Senate, representing the state of Ohio. I have exchanged telegrams with him about Zach and where he might go in the service to best utilize his unique skills, while keeping in mind your and Lizzie’s deep concern for his safety. “ John sipped some of the hot coffee and continued, “Sherman’s brother is an officer in the Western Army and…”

“You don’t mean William Tecumseh Sherman, do you, Jim?”

“The same,” John said.

“But I thought he was being treated for insanity. Didn’t I read a short while ago he was sent back East for treatment?”

“Quite right,” said Jim. “However, doctors quickly determined he was perfectly sound. He has some nervous twitches and a lot of nervous energy, but General Grant thinks he is an up-and-comer. The word is, he is a levelheaded general when he is under fire. His twitches go away and he is extremely competent.

“Furthermore, he wrote to his brother not long ago indicating his need for young men with Zach’s talents. Tom, I think if Zach would travel down to Fort Donelson or wherever Sherman might be, the general would make him a sharpshooter. That would mean he would not necessarily be in the front lines of this fighting. He would be one half-mile in the rear of the front lines, maybe behind a log, picking his targets one by one.”

Tom weighed what his friend had just said. His son was going to war one way or the other, and this idea seemed to greatly increase Zach’s chances of survival. On the other hand, he would be so far from home, probably over five hundred miles from home…

“Jim, I don’t like it, but it does offer some distinct advantages.”

“Sure it does, Tom, and it appears this Western front is going very well. Our men out there might just be able to stop the South from adequately supplying their armies. Why Zach will be home before the end of the year, ready to join you in your business. Next year at this time, he will have found a wife and you’ll be getting ready to become a grandfather.”

“Okay, okay. Before you have me in the grave, we’ll talk it over with Zach. Sure appreciate your help. Lizzie is worried to death.”

That evening at the supper table, Zach could tell his father had something to say. Whenever he did, he would be very quiet – as if he were trying to search for the right words and for the right time to say them. He was very quiet tonight.

“Was Mr. Luttrell here today, Father?” Zach asked.

“Yes, and that is what your mother and I want to talk to you about, Zach.”

Tom described the arrangements Luttrell had made.

“You mean I’m going out West? As part of Grant’s army? As a sharpshooter? Hoorah!!!! When can I go?”

“Just as soon as a letter of passage comes from General Sherman. But I think there is something very important you need to understand.” Tom sat back in his chair, glanced at Lizzie and continued, “Zach, you were born with a gun in your hand. You were shooting rabbits before you knew how to spell your name. You shoot birds, squirrels, groundhogs, fox, deer, anything that moves, and you are good at it, better than I ever was. But let me tell you something, Zach. When you put those spider lines on a man, a human being, you will feel differently. A human being is not a groundhog, not a squirrel hiding in a tree. Someday you will have your sights on an enemy soldier, and you will have the power to end that person’s life. That enemy soldier will be another human just like you are, with parents at home, maybe a girlfriend or wife. And you, by merely pulling the trigger, will be able to end that life.” Tom waited to let Zach absorb what he had just said and then continued, “When you realize what that means, what that really means, you may think differently.”

“I understand, Father, but maybe it will be shoot or get shot. I think I will do what I have to do to help quell this rebellion, and if that means taking another’s life, I will do it.”

Tom stood up from the table, indicating the meal was over. “You might be right, Zach, then again, you might be wrong. Whatever the case, your mother and I still don’t want you to go but…”

“I know, Father, but I’ll probably only be gone for a couple of months.”

“You write us often,” his mother said softly as she put her hand on Zach’s.

Chapter 3 – Luke

March 1862

Luke could feel the rhythm of the big mare as she galloped full speed down the rain-soaked cow path. As usual, he rode without saddle or bridle, guiding the horse with his feet and body. He urged her, “C’mon big girl, we gotta round up the cows before Pa figures out we’ve been lollygagging!”

Just as they rounded a slight bend, Luke saw a stream ahead. The heavy rain had swollen the normally three-foot-wide creek to over twenty feet. Luke leaned back, pulling the mare’s mane slightly to slow a bit. The horse eyed the swollen stream and Luke could feel her hesitate. With a gentle nudge and a reassuring pat, he urged her on. Luke leaned well forward and she leaped to the other side, rider and horse seemingly as one.

Clearing the stream, Luke tapped the mare’s neck on the left side to leave the path and head into the woods. He knew where the three cows were likely to go when it rained. Cutting through the woods would save a couple of minutes. The trees were thick and Luke let the sorrel mare thread her own way forward. She approached a low-hanging limb, and Luke had to slide down to the side of the horse. Hooking his right foot over the mare’s back and wrapping his arms around her neck, he gasped. “Gal dang it, when are you going to learn to give me a little more room?” Just as they got past the obstacle, Luke had to quickly right himself to avoid being walloped by another tree ahead.

Luke wasn’t sure, but he suspected the horse had done it on purpose. She was always cranky when heading away from the barn. He thought the horse might be a little smarter than he gave her credit. Turn her back toward the barn, and she always gave him more room; she seemed to have reserve speed only when returning home.

Finally they cleared the woods. Sure enough, the three cows were in a small meadow, munching on wild clover. When Luke appeared, they immediately lined up head-to-tail down the cow path and began moving toward the barn, about a mile’s walk away. Luke jumped off briefly to relieve himself and give his horse a breather. After several minutes, he remounted using his own peculiar, well-practiced method.

When Luke was about ten years old, his parents took him to a circus that was touring through eastern Tennessee. The circus had a trick rider who, when mounting a horse, stood on the right side facing forward, grabbed the mane with his left hand and somersaulted backwards, landing on the horse’s back, facing forward. It was the cleverest thing Luke had ever seen. Back home, he tried to do it, without success. Luke needed time to grow and strengthen his stomach muscles. He did sit-ups, as many as two hundred a day, every day. He learned quickly to do a back flip, but never got up high enough to reach the horse’s back. As he got older, he used a milking stool to give him the height he needed. Eventually, when he was about thirteen, he was able to do it without a stool. From then on, it was the way he preferred to mount a horse.

When the cows reached the overflowing stream, they needed a nudge to go into the water. It was not deep, and they waded across without difficulty. Suddenly, Luke saw movement in some low bushes. He pulled up short and waited for whatever was moving to show itself. After several moments, a red fox wove its way into view and Luke’s heart started pounding with excitement.

He quickly calculated the cows would get to the barn without any further prompting — it was not far away. In a split second, Luke decided to chase.

He tapped his heels on the mare’s haunches, leaned forward and slapped the left side of her neck. She responded instantly. In three powerful strides, she was at full gallop. The fox, hearing the sound of the hooves, quickly turned to run as it saw the large animal bearing down. The race was on.

Luke had no idea what he would do if he caught up with the fox. He had chased foxes before and all he knew was he loved the chase. He loved riding at breakneck speed — turning, swerving, jumping — doing whatever was necessary to stay close to the fox. He was addicted to the feeling he had when he communicated with his horse using only his body. The horse turned right when he leaned right. She would slow up when he leaned back, speed up as he leaned forward.

They zigged, then zagged. They made large circular turns left and right. The fox was wily and fast. Luke knew where the fox’s den was, and the fox was moving in that direction. Up ahead was a large briar patch. The fox slipped into it. Luke figured it would exit the briars in the direction of the den, so he veered the mare to the right, toward the far end of the patch. Sure enough, the fox exited the briars just before Luke got there and the chase continued.

Luke could sense the horse tiring. The fox went under a fallen tree. Just as the mare jumped over, the fox made a hard right. Luke leaned hard right and the horse responded. The grass was long and wet from the rain. The mare turned so sharply her hooves slid out from under her and she went down. Luke had felt her slipping, anticipated the fall, and raised his right leg to avoid getting it smashed under her body. Both were down. The horse frantically tried to get up, pawing the ground with her hooves to gain traction to right herself. She managed to get all four legs under her and stood without moving. She did not put any weight on her right rear leg.

Luke, having been tossed clear, also rose unsteadily. With a sinking feeling, he approached the horse. She had fear in her eyes. As he embraced her head, she calmed a bit. He ran his hands down her right side to assess the damage. Everything appeared normal, with no obvious broken bones. However, she was very reluctant to put any weight on her back right leg. He massaged the area for some time and eventually she was able to hobble forward. They started back toward the barn very slowly. Then he started to think about his father and how mad he would be when he found out about the mare’s injury. They had only two horses, an older draft horse and the sorrel. The draft was used to haul the wagon around the small farm and occasionally to take the buggy to town to get supplies. The sorrel was needed for many daily chores.

Their progress was tedious and Luke could tell the mare was in pain. With each hobbling step she sounded a low, guttural groan. When they finally got back to the barn, he was greeted by a red-faced, very angry father. It was ten in the morning and Luke was late by about two hours.

Luke felt very little attachment to the horse. They had named her “Bonnie,” but he did not consider her a pet. Farm animals — horses, cows — were an integral part of a farm’s operation, much like a buggy or a plow. They were one of the tools a farmer had at his disposal to do his work. The animals were cared for and fed, but they were expected to work and earn their keep. If an animal could not perform those duties, then that animal was a drain on the homestead.

Luke’s father took one look at the hobbled horse and another at Luke, who was bruised and scratched. His face turned even redder, “What the hell have you done this time? Do you have any idea how much we need that horse?” His raised his voice louder and louder. “How in the Sam Hill can I run this farm with this kind of behavior? When are you ever going to grow up, boy?” He pointed his finger at Luke, his hand shaking, his eyes looking big—ready to pop out. “Get your sorry ass over to the woodshed. Now.”

Luke walked slowly toward the woodshed. He knew he was in deep trouble. He had never seen his father so angry. To make matters worse, the cows must not have made it back to the barn as he had hoped. And he knew his riding after the fox had been foolhardy and immature. He had put the horse at risk when it was not necessary.

Luke’s father was a hard man who had lived a difficult life. In the summer of 1840, Jonas Lucas Pettigrew arrived in Crossville, Tennessee, a very small town near the western slopes of the Appalachian Mountains on the Cumberland Plateau. He was driving a team of draft horses that were pulling a small covered wagon in which he had placed all of his worldly belongings. He had previously worked on various farms and had saved his money, and now he meant to acquire some land and farm for himself. Jonas had lost his beloved wife and their child to childbirth. He had wandered aimlessly from odd job to odd job since her death, trying to piece together his life. The loss had left him withdrawn.

With the cash he had saved over the years, he purchased a ninety-six-acre plot of land that contained a decent four-room house near a small stream. He had a plow, two crosscut saws, hand tools and a bed. He hoped the cash he had left would carry him through until the farm could provide income.

He worked hard clearing trees and removing rocks to create tillable fields. He acquired a reputation with the folks in the area as being a very hard worker. From sunup to sundown, seven days a week, he worked the land. After two years, the farm started to take shape. And, in time, he met and began to court Anna Lambeth, the granddaughter of Samuel Lambeth, one of the first settlers in the area. They married, and in the spring of 1845 Anna gave birth to a strapping young boy, Lucas.

As he sat on a section of log that was waiting to be split, Luke considered what was coming. He tried to see things the way his father would. He knew his father’s first wife and child had died a long time ago, but his father never spoke of them to him. Maybe he did to his mother, Anna, but he never talked to Luke about his past.

Luke’s dog, Jeff — the one animal he cared about — came over and put his head on his lap, as if he sensed Luke’s sadness.

Luke also thought about the farm. The soil was not a rich loam. It had turned out to be thin, with few natural nutrients to grow crops. The soil was shallow, with more and more rocks appearing each year. It was as if the rocks grew during the winters and blossomed in the spring. He wasn’t certain, but he suspected that the farm’s income was causing a problem. While they had enough to eat, money seemed to be a continuous topic of conversation between his parents.

The farm was home to Luke. It was all he knew, and he loved his life. He tried to do whatever he was asked and, with only a couple of exceptions, he felt his parents were pleased. Every day was different with the kinds of experiences only a farm boy could appreciate. He was happy. He just wanted his life to continue as it was.

Inside the house, Jonas was trying to cool down and figure out what he had to do. He did not want to confront his son when he was angry. He had to give it some thought. On the one hand, the boy was just being a boy, enjoying the horse. His intentions were probably innocent, but he had clearly used poor judgment. On the other hand, he was another mouth to feed, and the farm was providing only the barest profit. He had discussed this situation with Anna, but she could not see or understand the problem. The land was becoming infertile, and either they would have to change from a crop farm to pure livestock, or they would have to move. Jonas, who was now in his late fifties, preferred the latter. But to move and start all over again would be very difficult at his age.

The continuing rift between the Northern and Southern states was an ongoing discussion between Jonas, Anna and to a lesser degree, Luke. Some of their neighbors were strong abolitionists and some very much believed it was all about states’ rights. Jonas and Anna deeply resented the radicals from both sides for stirring up so much trouble.

During the past year, most of their neighbors’ sons had signed up for Confederate service and Luke felt left out. Many of his best friends had joined up weeks and months ago, and he felt conspicuous, sensing that people might suspect he lacked patriotism, or even worse, was a coward. Luke knew the South had a much stronger cavalry and better riders than the North, and he preferred to become a cavalryman. He had heard of men like Nathan Bedford Forrest, and their swashbuckling daring naturally appealed to Luke.

When Jonas walked into the woodshed, his face was still red and tense, his lips were pinched, and dark bags hung down from his eyes. His jaw was set so hard the facial muscles contorted his appearance. He sat down on an old stool across from Luke and just stared down on the dirt floor for several moments. Finally Jonas looked up with a bereaved sadness.

“Luke, as you probably know, trying to eke out a living on our farm is becoming increasingly difficult. Each year we have had to draw from our now depleted savings just to buy seed for our next crops. We do not make enough to cover what it costs us, and I fear we have to make some changes if your mother and I are to make it through these times. Your reckless behavior this morning,” he continued, “has made our situation worse. We will probably have to put the mare down and we cannot afford to replace her.”

“But Pa,” Luke interjected, “she might be okay.”

“Let me finish, Luke. What I am trying to tell you is while your mother and I dearly love you, you are not contributing to this homestead. We have talked about this before…about some of the reckless things you do. Again and again, you act immaturely and put your mother and me at risk. You need to move on, Luke. Maybe when you grow up and become a man, you will come back and we’ll work together to make this a respectable farm. But until that happens, you are of no practical use to us. Who knows, maybe a couple of years in the army might just put some sense into that head of yours.” Jonas just sat on the old stool, looking down as if he had said all he was going to say.

Luke stared at his father, his mouth open. He was unable to speak. His mind was flooded with emotions. Rejection, sadness, anger, rebellion, all hit him at once. Grasping the gravity of what his father had just said, he let tears flow freely down his cheeks. For a long time, neither said a word. At length, Luke stood up and started walking toward the door. As he did so, he said, “I’ll be gone before morning.”

Jonas looked down at the dirt floor with his teeth still clenched, not moving.

The sun was high in the sky as Luke started walking toward town. He had not wanted to confront his mother, and walking out seemed the easiest thing to do.

As he passed the local post office, he stopped and looked at both sides of the front door. On the right was a bright new enlistment poster for the Confederate States of America and on the left was an old poster for the Union that had been mutilated and smeared with mud. He studied one, then the other, over and over.

The Union poster said something about saving the Union, while the Confederate poster brightly headlined, “Wanted: 100 Good Men To Repel Invasion.” Luke thought about the messages. Yes, it did seem like an invasion, he concluded. What right does the North have coming down here and trying to force us to stay in the Union? Remembering the phrase “independent states…” in the Declaration of Independence, any doubt he had about who was right and who was wrong went away and his mind was made up.

When he walked through the front door, the postmaster recognized him. “Hi, Luke,” he said. “No mail for the Pettigrews today.” He looked at Luke more closely, noticing his slumped shoulders and red eyes. Luke’s shirt had stains from his fall off the horse and was torn at the elbow. His face was covered with dust and dried streaks from his tears. His curly light brown hair was disheveled and caked with dirt. “What’s wrong, son? You look like you came out on the bad end of a fight with a polecat.”

“Fell off the horse,” was all Luke could manage. “How would I go about enlisting?”

The postmaster replied, “The Tennessee 28th is camped just west and a little south of here, and the sergeant is due here in a couple of hours. He’s always looking for recruits. We have quite a few boys from here in the 28th, and they’re all itching to get a chance to push the Yankees back north where they belong.”

Luke sat down on a stool next to an iron stove. He put his head down and covered his face with his hands. His head was reeling from his father’s words, “You need to move on…” His stomach started to churn and he felt nausea creeping in. He got up suddenly, walked out to the side of the front porch and vomited. He sat on the bench looking down on the weathered wooden floor, not seeing. He was numb, forlorn, rejected, alone.

As Luke sat, staring blindly, he remembered more of what his father had said, “Maybe when you grow up and become a man, you can come back…” He felt his face turn red and the hurt gave way to anger. “I’ll show him,” he thought, “I’ll go off to this goddamn war. I’ll be somebody. I’ll do some daring deed, save lives, be a big hero. He will live to regret what he said. I’ll prove him wrong, and he’ll beg me to come back. Maybe I won’t come back even if he asks me. I’ll prove him wrong! He will be proud of me and will regret what he said.”

Slowly, a sense of determination came over Luke. He’d wait for the sergeant from the Tennessee 28th to arrive.

To read more, visit the Home Again page.

We appreciate the use of the photo. Please visit Chattanooga and Beyond for more. . .

Leave a Reply