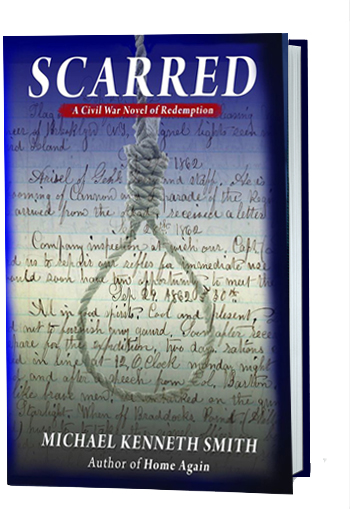

The following review for SCARRED A Civil War Novel of Redemption appeared in The Civil War Monitor.

Scarred is Michael Kenneth Smith’s emotional, fast-paced sequel to his debut Civil War novel Home Again. At the end of his first book, one of the protagonists, Federal sharpshooter Zach Harkin, is sent home following the Battle of Gettysburg suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). With Zach’s Confederate counterpart (Luke Pettigrew) from the first book dead, Scarred follows Zach’s struggle to find redemption for his wartime actions as well as his struggle to share his story fifty years later.

Scarred is Michael Kenneth Smith’s emotional, fast-paced sequel to his debut Civil War novel Home Again. At the end of his first book, one of the protagonists, Federal sharpshooter Zach Harkin, is sent home following the Battle of Gettysburg suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). With Zach’s Confederate counterpart (Luke Pettigrew) from the first book dead, Scarred follows Zach’s struggle to find redemption for his wartime actions as well as his struggle to share his story fifty years later.

The novel opens with reporter Chris Martin traveling to Knoxville, Tennessee, to interview the famous Zach Harkin—the sharpshooter who killed Albert Sidney Johnston at Shiloh. Writing for The New York World, Chris is eager to publish a career-changing article, especially one that highlights the men who courageously fought in the Civil War (5). Writing from the premise that one of the most effective treatments for PTSD is for the patient to discuss their traumatic experiences, Scarred traces Chris’s attempts to get Zach to talk about his time as a Civil War sharpshooter and where he disappeared to after his medical discharge in 1863. Little did Chris know that Zach’s story was less a story of courage and more one of suffering.

Knowing that the process would be painful, but determined to set the story straight, Zach decides to share his story with the young reporter. Returning to 1863, Zach tells of finding a photograph of his last victim’s family and his struggle to come to grips with his actions as a sharpshooter. Exhibiting symptoms of PTSD, Zach is mustered out and sent home. Back in Tennessee, Zach pledges to find his victim’s family and make amends. But unfortunately for the troubled ex-soldier, Confederate cavalry capture Zach and send him to Richmond as a prisoner of war. But rather than being sent to the hell that was Belle Isle, as were many enlisted men, Zach ends up in the infamous Libby Prison. Things get worse for Zach when he and his fellow prisoners are moved by train to a new prison—the dreaded Andersonville.

In his description of the Richmond prisons and Andersonville, the author demonstrates that he is quite knowledgeable about Civil War prison camps. History buffs and scholars alike will appreciate Smith’s dedication to historical accuracy. Echoing Civil War prisoners’ personal writings, the protagonist tells of how he and his fellow prisoners were tightly packed into railcars without adequate food and water during their transfer from Virginia to Georgia. Suffering from overcrowding, Zach ordered his comrades to gather toward the door when more prisoners were loaded to give the impression that the car was full, thus resulting in less men in the car (32). In their postwar memoirs, ex-prisoners frequently claimed to have used this technique to trick their guards.

Readers will especially enjoy Smith’s inclusion of well-known officers into the narrative, as this heightens the reading experience and helps anchor the story firmly into Civil War history. After escaping Andersonville and making it to Union lines, for example, Zach meets with General William Tecumseh Sherman and gets permission to continue his quest for redemption. After traversing through enemy territory and pretending to be a wounded Confederate soldier, Zach finally makes it Milledgeville, Georgia, to meet the family in the dead Confederate’s photo—Martha Kavandish and her son Tommy. But the war is hell and it eventually comes to Milledgeville. Once again Zach is forced to fight, this time for love.

Although less a battle-filled war novel than its prequel, Scarred illustrates how the violence of war is not just limited to the battlefront (and how it continued to affect those involved long after the guns fell silent). Smith’s almost cinematic novel could easily be the true story of a Civil War prisoner of war. Historians have recently demonstrated that both Union and Confederate veterans, especially ex-prisoners, struggled to reintegrate into civilian society after the war; while not all were as hesitant as Zach, many did not share their stories until the turn of the century. As a result, the story of Zach’s quest for redemption and closure will interest and surely entertain all those fascinated by the Civil War, from professional historians to history buffs.

While Smith has clearly done his research, the book contains some issues that historians may find distracting. The most significant is Zach’s sympathy for Captain Henry Wirz, commandant of Andersonville. Unlike the sources written by Andersonville survivors, Smith’s protagonist does not blame Wirz for the horrific conditions of the camp. Rather, Zach sympathizes with Wirz—a feeling that causes the fictional editor of The New York World to question Chris’s publication, fearing that his subject is trying to rewrite history (91). While historians continue to debate over who was to blame for the deaths of nearly 13,000 men in Andersonville, Smith’s apologetic tone is distracting and incongruous with real prisoners’ writings. But as the work is a historical fiction, the reader can overlook this incongruity and enjoy the book for its other offerings. Overall, Smith provides an intense reading experience that leaves the reader wanting more.

Angela Riotto, an historian of the Civil War prisoner of war experience, is finishing her Ph.D. at the University of Akron.

Leave a Reply